The nature of the person who makes the clothing is also an integral factor. What sort of life does he lead? That approach to life is clearly revealed in the clothing. The process might begin with a line drawn boldly, sincerely, on a scrap of paper by a practiced hand working like a finely tuned piano. This line may then be embodied in a fabric with a certain weight. In time it will be stretched into a garment, and there it takes on a life of its own. It begins to sing. It sings of indiscretions from the night before, it sings of the morning’s sunlight filtered through the trees.

In the end the garment leaves the purview of he who designed it. In time it will experience a chance encounter with one who will wear it. Will that person who dons the garment hear my song as hidden within it? That issue, in fact, is unimportant. The intentions of he who made the garment are nothing in comparison to the lived experiences of the person who wears it, nothing in comparison to the stolen pleasures enjoyed with a mysterious woman.

For example, the theme of my Paris collection for Autumn-Winter 1986-87 was the paradox of obsessions with the perfect body. I announced that I would make garments that resembled a pencil-case. I would burst the illusions of the women who wore them by turning the garments themselves into objects of appreciation. I imagined it as clothing designed with a strong graphic element.

This was my way of posing a question to women. “Are you right to obsess over the perfect body?” Then why not get in shape, exercise good posture, and try wearing these clothes? As mistaken as your assumptions might be, once you put on these garments, you will see that they work. It was a nasty trick to play, and I thoroughly enjoyed the thrill of it. Is the Western body type the only one that is beautiful? In my personal opinion, it is the silhouette that sets the tone and reflects the attitude.

The obsession with the overall proportions at the expense of everything else is proof of how extensively western aesthetics have poisoned our sensibilities. Japanese culture of long ago found beauty in the nape of the neck and in the curve of the back. At some point the sensitivity to the beauty in these things withered, and both men and women became blind to them. I have personally always found the greatest charm in the long, sweeping curve from the ribcage past the waist and down to the hips. It is the most subtle line, curving like a serpent.

The phrase “to put on clothing” is rendered in the Japanese language as, literally, “to pass one’s arms through the sleeves.” The phrase perfectly captures the importance of a sleeve’s presence. Within the aesthetics of Western structures, the conventions of design relegate the sleeve to the role of a mere supplement. In placing the sleeve in a more central role, however, one moves closer to the kimono.

The armhole is where the sleeve departs from the bodice, I refer to that point as the intersection. The distance between that intersection and the bodice determines the look and outcome of a garment in a most fundamental way. One might imagine it is a choice between a grand intersection of two avenues or a narrow crossroads of two alleyways. Either way, intersections are the point at which people meet, they are the point at which people part.

When a man drops his guard to reveal what is truly in his heart, it is a form of confession. In a certain sense, a man’s back tells a silent story, his shoulders carry all the treasures of life.

The shapes of the human shoulder are as numerous as the types of faces. Ready-to-wear clothing must somehow squeeze them all into a single appealing form. One should seek a shoulder span and slope that is an ideal match for the philosophy behind the garment as a whole, and attach the sleeves based on that.

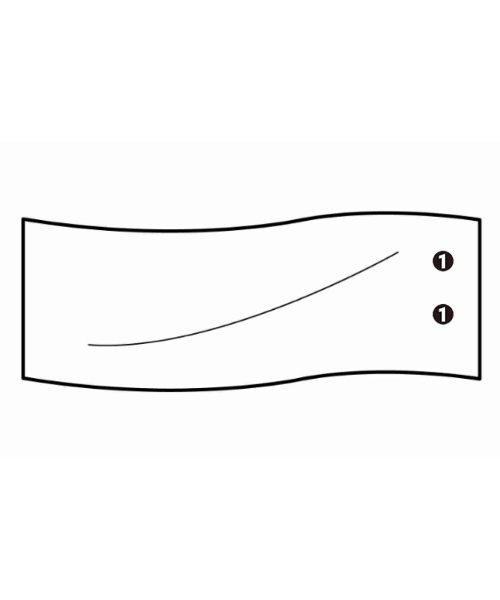

The pleasures of attaching sleeves are like those of building tunnels. Basically, the sleeves should be slightly towards the front and joined to the bodice, like two curved tunnels. Though it depends to some extent on the nature of the particular garment, one should always beware of the following. Does the garment lose its shape and lay flat when the arms are lowered to the sides? Are the armpits pulled tight when the arms are moved? In addition, the garment should float well even without the use of pads. One should think of the slope of the shoulder, the armhole, and the peak of the shoulder as three lovers destined to remain locked in a tumultuous relationship.

The manner in which a sleeve is attached is the very lifeblood of a silhouette. The shape of it must be envisioned in some detail at a very early stage, even before the overall form of the garment is decided. It is a crucial element because clothing hands from the shoulders, and the angle at which they slope determines all functions of the garment.

There are essentially two designs for men’s tailored jackets. One has the slope of the shoulders and the curve of the sleeves designed to match the body type of a particular individual, as in the manner of the draping of the Victorian era. The other, employing modern techniques, shapes the garment according to a pre-established, idealized conception of the male form. Here pads are used to supplement areas in which a particular body does not subscribe to that idealized form. One might think of this as a package design based on aesthetic conventions.

While the styles of women’s clothing are not as formalized as men’s, one might recognize certain similarities. The dolman and raglan sleeves so often used in women’s clothing today, for example, had their basic contours shaped by war. The raglan sleeve was invented by the English General Raglan, who lost his right arm in the Battle of Waterloo. With a seam that runs diagonally from the underarm to the neckline, the sleeve and shoulder are incorporated as a single unit. It is designed for ease of motion even, for example, in injured soldiers.

Soldiers take silent cover in a trench as the rain pours down from above. There are no seams in the shoulders of their garments for this helps to keep them dry.

My approach to men’s clothing is to imagine what I would wear in order to express my current frustrations and thoughts about the world at this present juncture. In other words, in the case of men’s fashion, the clothing matches my position, oddly eccentric as it may be.

I explore my quirky, rebellious self without defending or denouncing it. I simply put it on display. When I am unhappy, my position emerges as nothing more than idiosyncrasies or mannerisms. I do not like such results, but the fact of the matter is that making clothes requires one to continually express oneself aggressively, and if that means that disappointing sides of the self are sometimes revealed in the process, so be it.

Men are ridiculous, aren’t they?

The more professional one becomes, the less one wants to use buttons. Taken to the extreme, one works for a garment that closes in the front even without the aid of buttons. That is a truly good design.

Is it not crude and grotesque to pick one’s nose while Socrates exorcises his demon and speaks of the divine soul? Can it be called anything other than vulgar when Diogenes lets a fart fly against the Platonic theory of ideas—or if fartiness itself one of the ideas God discharged from his meditation on the genesis of the cosmos? And what is it supposed to mean when this philosophizing town bum answers Plato’s subtle theory of eros by masturbating in public?

To embody a doctrine means to make oneself into its medium. This is the opposite of what is demanded in the moralistic plea for behavior guided strictly by ideals. By paying attention to what can be embodied, we remain protected from moral demagogy and from the terror of radical abstractions that cannot be lived out.

In a culture in which hardened idealisms make lies into a form of living, the process of truth depends on whether people can be found who are aggressive and free (“shameless”) enough to speak the truth.

Initially, as for example in Old High Germany, it meant a productive aggressivity, letting fly at the enemy: “brave, bold, lively, plucky, untamed, ardent.”

The prototype of the cheeky is the Jewish David, who teases Goliath, “Come here, so I can hit you better.”

“When Plato put forward the definition of the human as a featherless biped and was applauded for it, he tore the feathers from a rooster and brought it into Plato’s school saying, ‘That is Plato’s human’; as a result, the phrase was added: ‘with flattened nails’”

An essential aspect of power is that it only likes to laugh at its own jokes.

Diogenes may well be a figure whose public appearance can be understood in terms of the competition with Socrates; his bizarre behavior possibly signifies attempts to outdo the cunning dialectician with comedy. But this is not enough: kynicism gives a new twist to the question of how to say the truth.

neither Socrates nor Plato can deal with Diogenes — for he talks with them “differently too,” in a dialogue of flesh and blood. Thus, for Plato there remained no alternative but to slander his weird and unwieldy opponent. He called him a “Socrates gone mad” (Socrates mainoumenos). The phrase is intended as an annihilation, but it is the highest recognition. Against his will, Plato places the rival on the same level as Socrates, the greatest dialectician. Plato’s hint is valuable. It makes it clear that with Diogenes something unsettling but compelling had happened with philosophy.

In idealism, which justifies social and world orders, the ideas stand at the top and gleam in the light of attentiveness; matter is below, a mere reflection of the idea, a shadow, an impurity. How can living matter defend itself against this degradation? It is excluded from academic dialogue, admitted there only as theme, not as an existent. What can be done? The material, the alert body, begins to actively demonstrate its sovereignty. The excluded lower element foes to the marketplace and demonstratively challenges the higher element. Feces, urine, sperm! “Vegetate” like a dog, but live, laugh, and take care to give the impression that behind all this lies not confusion but clear reflection.

Now, it could be objected that these animal matters are everyday private experiences with the body and do not warrant a public spectacle. That may be, but it misses the point. This “dirty” materialism is an answer not only to an exaggerated idealism of power that undervalues the rights of the concrete. The animalities are for the kynic a part of his way of presenting himself, as well as a form of argumentation. Its core is existentialism. The kynic, as a dialectical materialist, has to challenge the public sphere because it is the only space in which the overcoming of idealist arrogance can be meaningfully demonstrated. Spirited materialism is not satisfied with words but proceeds to a material argumentation that rehabilitates the body. Certainly, ideas are enthroned in the academy, and urine drips discreetly into the latrine. But urine in the academy! That would be the total dialectical tension, the art of pissing against the idealist wind.

To take what is base, separate, and private out onto the street is subversive.

Ethical living may be good, but naturalness is good too. That is all kynical scandal says. Because the teaching explicates life, the kynic had to take oppressed sensuality out into the market. Look, how this wise man, before whom Alexander the Great stood in admiration, enjoys himself with his own organ! And he shits in front of everybody. So that can’t be all that bad. Here begins a laughter containing philosophical truth, which we must call to mind again if only because today everything is bent on making us forget how to laugh.

He, who provided the impulse for kynicism, introduced the original connection between happiness, lack of need, and intelligence into Western philosophy — a theme that can be found in all vita simplex movements in world cultures.

Citizens struggle with the chimera of ambition and strive for riches that, in the last analysis, they cannot enjoy any more than what is enjoyed in the elementary pleasures of the kynical philosopher as a daily recurring matter of course: lying in the sun, observing the goings-on in the world, being glad. and having nothing to wait for.

The fascination of the kynical mode of life is its astounding, indeed almost unbelievable serenity. Those who have subjected themselves to the “reality principle” watch, perplexed and annoyed that at the same time, but also fascinated, the activities of those who, so it seems, have taken the shorter path to authentic life and who avoid the long detour of culture to the satisfaction of needs. “Like Diogenes, who used to say, it is divine not to need anything, and semidivine to only need little”

The pleasure principle functions for the wise in a way similar to that for normal mortals, however, not because they get pleasure from the possession of objects, but because they realize how dispensable objects are, and thus they remain in the continuum of vital contentedness.